Para abordar este nuevo tema del programa de Seconde, la Sra. Cabin, profesora de inglés, decidió presentar a sus alumnos el trabajo de Edward Hopper, pintor estadounidense que inspiró a muchos artistas (artistas urbanos, pintores y también cineastas).

Por lo tanto, estudiaron las características del estilo Hopper al comparar pinturas. Los alumnos identificaron fácilmente su juego en las luces, el claroscuro, los elementos geométricos recurrentes (a menudo símbolos de confinamiento), pero especialmente la pesada atmósfera de soledad y la impresión de introspección de los personajes, a menudo aislados.

Hopper pintó extensamente durante los tiempos sombríos de la Gran Depresión y la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

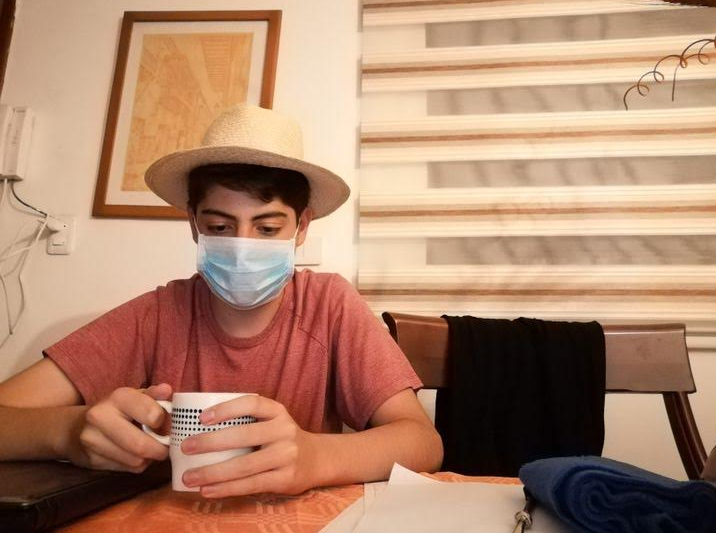

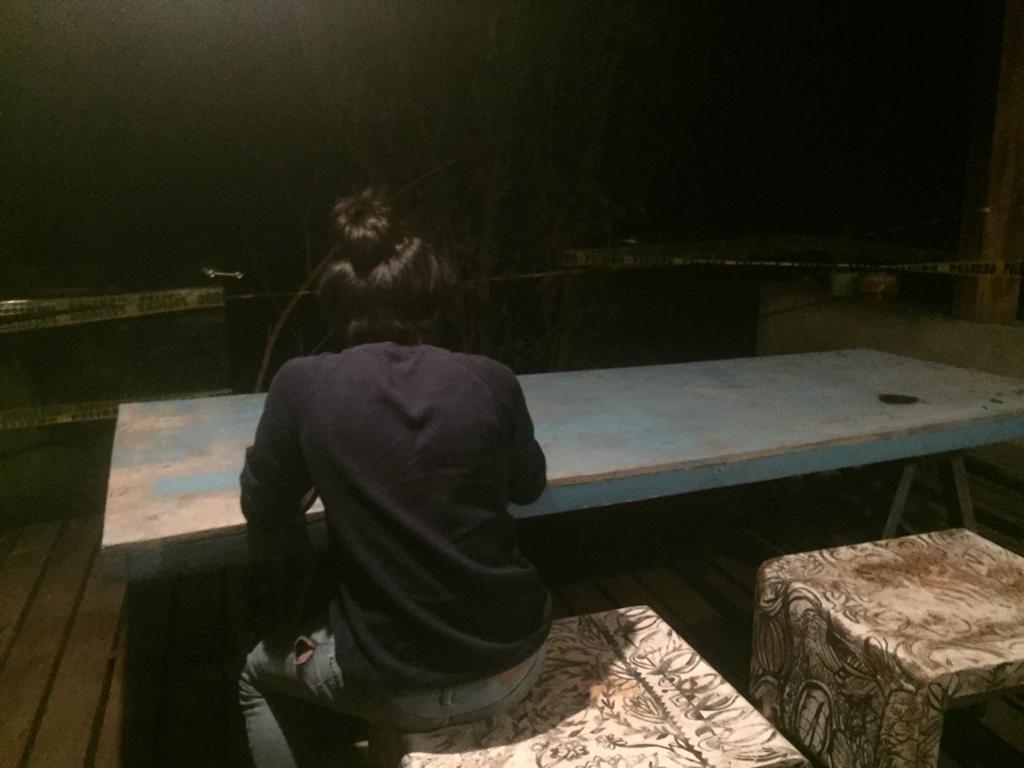

Por una parte, los alumnos de Seconde A y C tuvieron que imaginar los pensamientos de un personaje, y por otra parte proponer una foto de puesta en escena que refleja el espíritu de las pinturas de Hopper.

Estas son las fotos que les invitamos a descubrir a continuación.

Algunos alumnos querían reproducir una pintura, otros dieron rienda suelta a su inspiración.

Estábamos lejos de imaginar que el trabajo de Hopper sería muy actual y citado en los medios en el contexto de confinamiento que estamos viviendo con la pandemia de Covid-19.

‘We are all Edward Hopper paintings now‘: is he the artist of the coronavirus age?

The Guardian, Jonathan Jones, Fri. 27 Mar. 2020.

With his deserted cityscapes and isolated figures, the US painter captured the loneliness and alienation of modern life. But the pandemic has given his work a terrifying new significance.

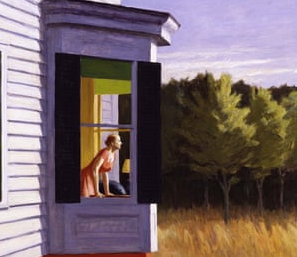

Eerie echoes … Edward Hopper’s Cape Cod Morning, 1950.

Who can fail to have been moved by all the images of people on their doorsteps clapping for the NHS last night? They filled TV screens and news websites, presenting a warming picture of solidarity in enforced solitude – all alone yet all together. But there are some far less reassuring images circulating on social media. Some people are saying we now all exist inside an Edward Hopper painting. It doesn’t seem to matter which one.

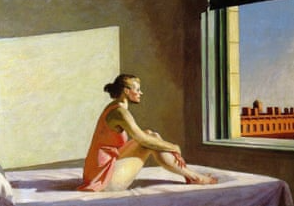

I assume this is because we are coldly distanced from each other, sitting at our lonely windows overlooking an eerily empty city, like the woman perched on her bed in Morning Sun, or the other looking out of a bay window in Cape Cod Morning.

“We are all Edward Hopper paintings now,” according to a WhatsApp compilation of Hopper scenes: a woman alone in a deserted cinema, a man bereft in his modern apartment, a lonely shop worker and people sitting far apart at tables for one in a diner. As is the way with memes, it’s hard to tell if this is a serious comment or a glib joke with a side order of self-pity.

Coldly distanced … Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, 1942.

But let’s take it seriously. If we really are all Edward Hopper paintings now, a crisis of loneliness is impending that may be one of the most fraught social consequences of Covid-19. The loss of direct human contact we’re agreeing to may be catastrophic. This, at least, is what Hopper shows us. This painter born in New York state in 1882 made solitude his life’s work. In the 1920s, while F Scott Fitzgerald was chronicling the party animals of the jazz age, he painted people who looked as if they had never been invited to a party in their lives.

Modern life is unfriendly in the extreme for Hopper. It doesn’t take a pandemic to isolate his poor souls. Cold plate-glass windows, towering urban buildings where everyone lives in self-contained apartments, gas stations in the middle of nowhere – the fabric of modern cities and landscapes is for him a machine that churns out solitude. Nor do his people find much to do with themselves.

Atomised individuals … Edward Hopper’s Morning Sun, 1952.

It’s images of Hopper’s horrors that are being shared today– and that isn’t too strong a word. One of the painter’s biggest fans was Alfred Hitchcock, who famously based the Bates mansion in Psycho on a Hopper painting of a strange old house isolated by a railroad.

We all hope to defy Hopper’s terrifying vision of alienated, atomised individuals and instead survive as a community. But, ironically, we have to do that by staying apart and it may be cruelly dishonest – the empty propaganda of the virus war – to pretend everyone is perfectly OK at home.

For the message of Hopper is that modern life can be very lonely. His people are as isolated among others in a diner or restaurant as they are at their apartment windows. In this he is typical of modernist art.. In normal times, we sit alone in cafes, too, except we’ve now got mobile phones to make us feel social. The fact is that modernity throws masses of people into urban lifestyles that are totally cut off from the gregariousness that was once the norm.

In pre–industrial times, Bruegel’s scenes of peasant life show a world in which it was practically impossible to be alone. Kitchens are crammed and carnivals a nightmare for anyone practising physical distancing. Looking at Bruegel, you can see why many people in Britain were so reluctant to give up pubs – those last refuges of the Bruegelian past.

We choose modern loneliness because we want to be free. But now the art of Hopper poses a tough question: when the freedoms of modern life are removed, what’s left but loneliness?